Transnationalism is a concept that provides elites with both an empirical tool (a plausible analysis of what is) & an ideological framework.

Institutions and Incentives, All the Way Down

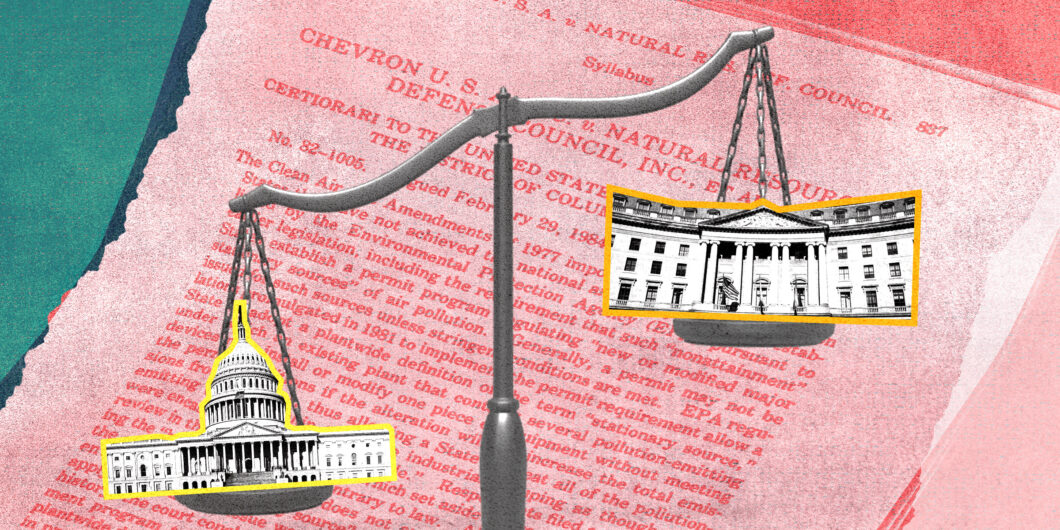

I commend Adam J. White on his characteristically thoughtful, judicious essay. I take this opportunity to pursue my dear friend’s premises—unstated, but obvious—a bit further and perhaps to an end that may be grimmer than Adam lets on. He expresses a guarded hope that Chevron’s demise will be conducive to “good, steady, constitutional administration.” That is possible, I suppose; but not bloody likely.

The central premise—Adam’s premise, and that of a gigantic Chevron literature I’ve never bothered to read—is that rules and rule changes rattle through institutions. Not that Congress or agencies necessarily have any great regard for judicially imposed rules or rule-conforming behavior: that would be a very odd presumption vis-à-vis legislators with power to make the rules, or with respect to the folks who currently run the FTC or the EPA. It’s rather a matter of marginal incentives. Chevron deference, Adam stresses, for good but mostly for ill encourages certain forms of (executive, legislative, judicial) conduct and discourages others. Change the rule: what follows, incentive-wise and behaviorally? The question calls for speculation. Outside a trial court, though, it is permissible and worth asking. Two related problems, however, confound the inquiry. Call them evasion, and aggregation.

Evasion. “Show me the incentives, and I’ll show you the outcome,” the late Charlie Munger famously averred. That may well be right, or at least a good first approximation, with respect to business management. Government? Not so much.

Take the most direct rule-to-incentives-to-outcome connection: court to agency. Court ends Chevron deference. In response to stricter legal oversight the agency does—what?

Intuitively, we assume the agency wants to protect its programs and agenda against judicial review and reversal (because it wants to protect its turf, or because congressional and private constituencies demand that course, or for some other reason). But even that isn’t necessarily true under all conditions. Over decades, the EPA in particular has often sought to put itself under court orders in lawsuits instigated by advocacy groups, the better to insulate itself against congressional and industry opposition. Chevron’s demise might well encourage that m.o. (“Sorry: here at the EEOC and the Office for Civil Rights, having been sued by credible constituencies spanning half the alphabet, we must go the full Bostock.”) Any which way, the outcome has little to do with the train from rule to incentives to institutional conduct, and everything to do with the political constellations of the day.

On Adam’s more hopeful note, agencies may respond to tighter judicial controls by improving their product by supplying reasoned legal analysis and solid evidence (though perhaps, Adam cautions, too much of it). Possibly. Then again, they may further immunize their actions against judicial control. An agency may bludgeon regulated parties into settlements that then shape industry behavior: that’s the SEC’s and the CFPB’s model. It may propose rules that would hardly pass judicial muster but nonetheless compel industries with long investment horizons to comply in the here and now, on the off chance that the rule just might survive: that’s the EPA’s model. An agency may never commit a reviewable act and instead publish “guidances” or “dear colleague” letters: that’s the FDA, and the OCR, and numerous other agencies.

All those forms of agency conduct are common even under Chevron’s forgiving regime. Tighten judicial oversight: the result may well be yet more regulatory dark matter.

Aggregation. We tend to think in aggregate institutional terms: “the Congress,” “the Executive,” “the Judiciary.” Yet none of them is a unitary actor. Even the Administrative Procedure Act’s “agencies” aren’t unitary actors: they have heads, enforcement divisions, adjudicators, rule writers, sometimes even economists. All the individual actors have incentives of their own.

In a particularly insightful part of his essay, Adam brings that thought to bear on courts and agencies. Chevron’s demise, he suggests, will force courts to think harder about long-submerged questions. To whom and to what, exactly, do courts defer when they burble about an agency’s “expertise” or (on many Chevron accounts) the agency’s greater “democratic accountability,” relative to independent courts? If courts do zero in on those questions, what would that mean for agencies’ internal operations? Does an agency head actually have to do the interpreting, or scrutinize “expertise” that may be mere pretext for already-made decisions?

Those questions point back to my earlier point: agencies might respond by adopting more rule-conforming modes of operation, or by further rewarding internal actors who are good at producing regulatory dark matter that evades judicial review altogether. There’s no way of telling.

I have everything riding on a jurisprudence that reflects a Hamiltonian realism about politics without romance.

No such difficulty, alas, attends Adam’s fond hope that Chevron’s demise might at last spur congressional intervention. If agency regs go down in courts that have ceased to defer to agency interpretations of gaseous, inchoate, blunderbuss statutes, Congress—the theory goes—can no longer paper over disagreements by delegating the real rulemaking power to agencies. The hope is that more stringent judicial review will incentivize Congress to legislate, at long last. Chevron’s critics, Adam emphasizes, “have everything riding on it.”

Perhaps so; and Adam notes—correctly, to my mind—that Chevron’s demise may well come to be accompanied by a judicial nondelegation doctrine with teeth. (It already exists in the form of the “major question” doctrine.) Still, I deem this a case of a failure to disaggregate. The Constitution may well envision a “collective Congress.” But that body—a deliberate, structured body that responds coherently to a changed legal and institutional environment—has long ceased to exist. There are only individual legislators, and we can be very confident of the one incentive that trumps all others: reelection. Legislators who act otherwise won’t be legislators for long. Those who put a premium on deliberation and compromise will quit and, for the most part, have already done so. Farewell, Mike Gallagher. We have seen the future, and she is Marjorie Taylor Greene.

In a post-Chevron world, then, the” hydraulic forces” (Adam’s term) of increased judicial oversight will have to play out elsewhere, and differently. One possible result is simply less law and less roving agency authority, which might not be a bad thing. Then again, we may see yet more direct White House control: the President is not an “agency,” and therefore exempt from APA review. But who knows? The only certainty is continued congressional incapacity.

Take-Aways. Most of the foregoing will meet with Adam’s vehement agreement; he acknowledges many of the difficulties in his essay. To that considerable extent, I have been unfair to Adam and lapsed into my usual mode of discourse: kvetching. I conclude on two thoughts, which may or may not find Adam’s approbation.

One, the focus on “rules and incentives” is the right way to think about the administrative state, and law more broadly. But the incentives in this setting are quite multifaceted and complex; and among them is the incentive for wayward, non-conforming behavior. In important opinions and law review articles, the late, much-missed Judge Stephen F. Williams arrticulated the basic calculus: judges should push hard on the law, but not to the point of further incentivizing the very behavior that the rules are meant to block. That insight is worth a thought in the Chevron context.

Two, the time may have come to think seriously about Administrative Law Without Congress, as Ashley Parrish and I put it some years ago in a provocatively titled article. (We may decide to update that piece because agency behavior has since become way worse.) The thought is heterodox, but also quite originalist.

“The will of the Congress must prevail”: that is the irreducible premise of public law since the New Deal—of Erie Railroad (1938), and of the administrative law that Felix Frankfurter and the geniuses of the Legal Process school bequeathed us. Weirdly, it is also the key premise of (drumroll) Chevron—and (drumroll again) of the “textualist” jurisprudence that finds fault with Chevron. I find that premise—courts as the legislature’s handmaiden; judges as nudges of detailed legislation—very problematic.

“It is not with a view to infractions of the constitution only” that we want to have an independent judiciary. That judiciary also plays an essential role in “mitigating the severity and confining the operation” of “unjust and partial laws,” prompted by “ill humours in the society.” While such judicial interventions will “displease those whose sinister expectations they may disappoint, they must command the esteem and applause of all the virtuous and disinterested.”

Adam White can recite those passages (here slightly edited) from memory: they’re from Hamilton’s Federalist #78. The great Alex fully expected that there would be lots of designs for “unjust and partial” laws; ill humors run through most of society, most of the time. That also tends to be my view. Thus, unlike many Chevron critics, I actually do not have a lot riding on the bet, or a romantic hankering, for a responsible Congress. I have everything riding on a jurisprudence that reflects a Hamiltonian realism about politics without romance.